Tempting Intemperance

The Niagara Region is best known for its rich history and wines, drawing thousands of tourists each summer. I began to consider the locals and how long they have equally enjoyed and indulged in the wines and spirits of the area. What I have come to discover is a relationship that is as sweet as ice wine, and as bitter as cabernet sauvignon. Taverns, inns, and public houses were routinely established before government and religious buildings, due to their significance as community hubs and transportation networks. Drinking establishments acted as lodging and meeting spaces where individuals could not only seek refreshment and entertainment but also fulfil their social needs. Such establishments allowed for an exchange of ideas that fuelled the formation of both communal and national identities in Upper Canada. Thus, public houses have been integral to the formation of community and social identity. Nevertheless, an identity dependent on overconsumption would soon prove futile. By the mid-19th century, the negative effects of overconsumption could not be ignored, with many across the nation calling for complete abstinence. For many who depended on these public houses for work and sustenance, the threat of a dried supply line could be detrimental.

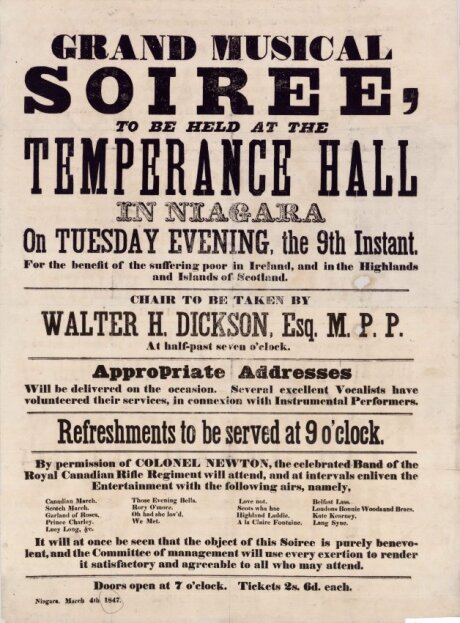

From 1792 to 1796, the Town served as the first capital of Upper Canada, attracting government officials, merchants, and visitors alike. In 1794, six taverns served the growing settlement. On the eve of the War of 1812, twenty-one people held licences to operate taverns. For perspective, there were about 500 people living in Town when the Americans retreated and set the community ablaze. Notions of abstinence began in March 1813, when Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe and his assembly discussed the matter of saving important provisions (Riddell, 1920). Shortly after, an act was passed to authorize the person administering the government of the province to prohibit the exportation of grain (and other provisions), as well as the distillation of spirits, strong waters, and low wines (1813, 53 Geo. III, C. 3). The quality and production of grains had greatly diminished during the war as many farming-class men had hung up their sickles for sabres in the Upper Canadian militias. Military and Civil Commander of Upper Canada, Gordon Drummond, issued an 1815 proclamation to “Prohibit the Distillation of Spirits, strong Waters and low Wines from any Wheat, Corn or other Grain, Meal or Flour...” within the province (NOTL Museum Collection, 987.5.462). It is likely that this proclamation aimed to resolve the agricultural supply issues resulting from the war, as this ban was not an official decree. Ironically, our museum’s collection houses several invoices from British and Canadian officers seeking reimbursements for the purchasing and consumption of alcohol. This lodging and bar bill dated to 1814 (see Fig. 1) indicates that it had been customary to bill the British army for a company’s refreshment. Our collection does not have any receipts for liquor or spirits following Drummond’s declaration, though it is possible that this habit continued through the final stages of war. Nevertheless, the prohibition laid the seeds for temperance movements that began sprouting throughout the provinces.

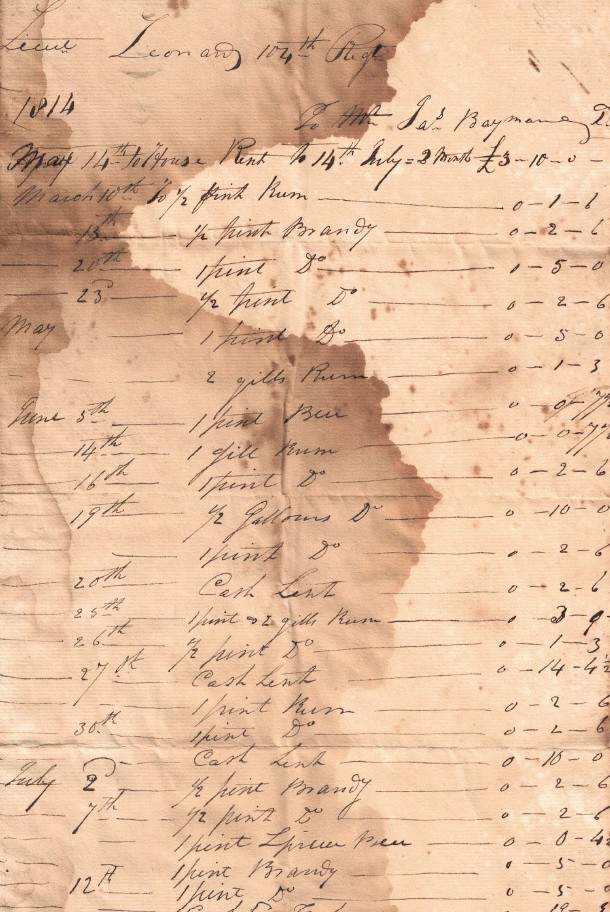

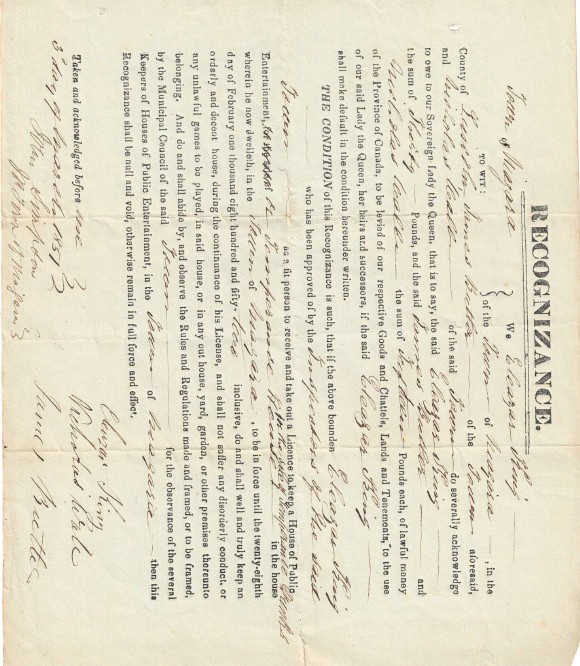

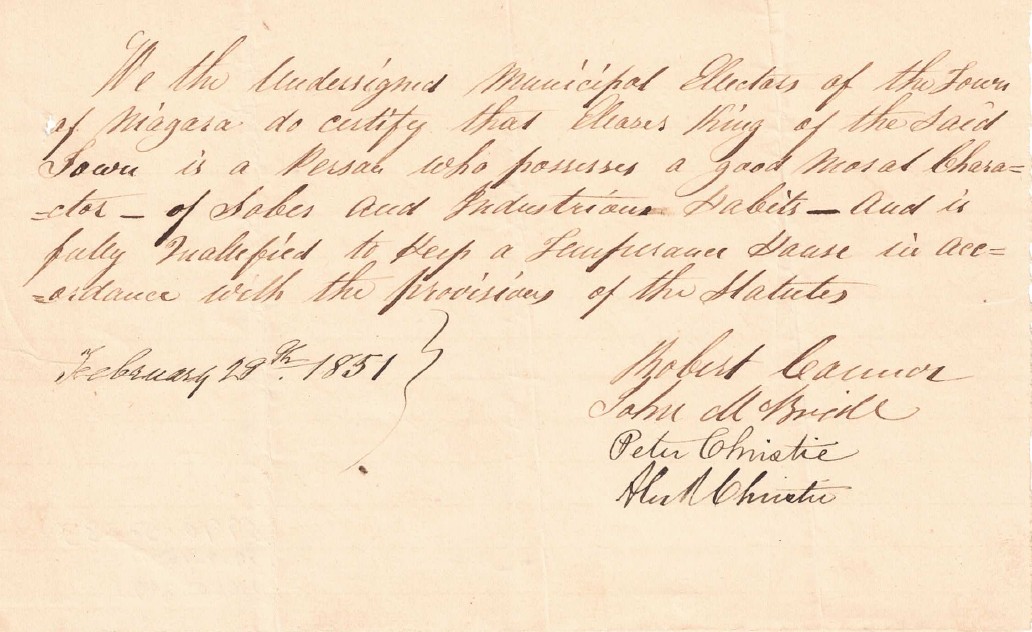

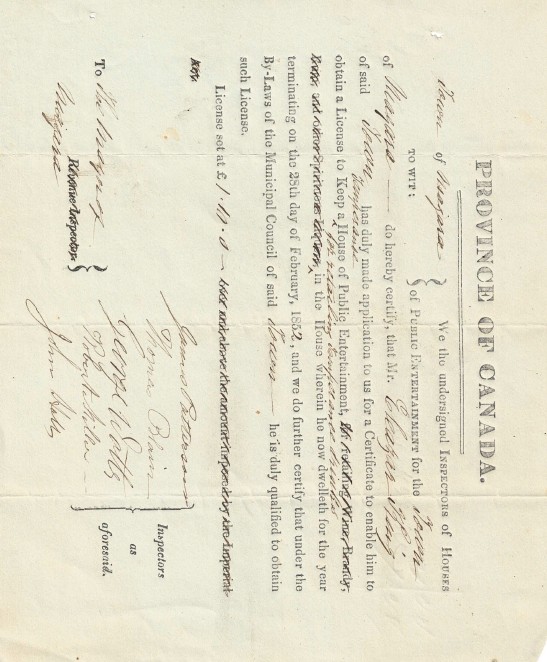

Issues of intoxication were apparent to travellers in the region; writer Anna Jameson was confounded by “a good deal of drunkenness and profligacy” that plagued Niagara in the mid-1830s (Jameson, 1838, p. 146). By 1820, the town of Queenston had thirteen inns and by 1858, the town of Niagara had twenty-seven public houses in operation (NOTL Museum Collection, 990.5.346). In fact, overconsumption was so widespread in Upper Canada that some historians have considered it to be the most intoxicated nation in the world up until the mid-19th century (Riddel, 1920). Upper Canada had begun its gradual fall from grace with the advent of the Temperance Movement in the late 1820s (Decarie, 2020). As early as the 1830s, meetings were held to form a temperance organization (NOTL Museum Collection, 987.5.200). The Niagara Temperance Society was active throughout the 1840s and established the first Temperance Hall in the Province. The Hall hosted soirees, concerts, and served non-alcoholic refreshments. Likewise in 1851, Eleazer King took out a license for a temperance house to provide alternatives to the evils of drunkenness (see fig. 2, 3, and 4). The Society was successful enough to publish a newspaper titled ‘The Fountain.’ Vol. 1, No. 2 published on March 26, 1847, is the only proof of the paper’s existence. Janet Carnochan recorded this information in her historical notes. Regarding the Society and its organizations, she writes: “How long the paper was in existence is not known but it shows that Niagara must then have had a strong temperance element to induce the publication of such a paper. Many notices…refer to meetings to be held in the Temperance Hall. We can now boast of no such building” (NOTL Museum Collection, 982.419.1).

As Carnochan inferred, numerous community members felt the need to establish a “strong temperance element” in town. Boozing had become so entrenched within the community’s identity that a petition was presented to the Town Council in 1855, stating that overconsumption was “a great moral and social evil, destructive of health, virtue, and happiness” only capable of producing “disease, lunacy, and crime” (NOTL Museum Collection, 990.5.380(A&B)). The government first responded to the expanding Temperance Movement via the Dunkin Act of 1864, which allowed any county or city to ban the sale of alcohol through a referendum. A decade later, the Canada Temperance Act of 1878 (or Scotts Act) passed, giving authority to municipal governments to ban the sale of alcohol. Unfortunately for local temperance groups, they lacked the numbers to achieve a majority vote in Niagara.

The push for prohibition would continue into the 20th century, coming to a head once again during the war years. Support for temperance in Niagara was outweighed by an appetite for intoxication. This hunger was exacerbated by the Prohibition in 1917, where NOTL’s history with wines and spirits becomes even more convoluted. To discuss this history in one blog post has proved impossible, unless our readers would enjoy a full dissertation on the matter. Don’t worry, I won’t leave you high and dry! For now, I will leave you to consider our early history with alcohol and how it fits into our modern context. Cheers!

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

References

Decarie, G. (2020). Temperance Movement in Canada. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/temperance-movement

Jameson, Anna. (1838). Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada. Saunders and Otley. https://archive.org/details/winterstudiessum02jame/page/146/mode/2up?q=profligacy

Merrit, Richard. (1991). “Early Inns and Taverns: Accommodation, Fellowship, and Good Cheer,” in The Capital Year: Niagara-on-the-Lake, 1792-1796. Toronto and Oxford Dundurn Press.

Riddell, William R. (n.d.). “The First Canadian Prohibition Measure” Retrieved from https://ia600607.us.archive.org/view_archive.php?archive=/8/items/crossref-pre-1923- scholarly-works/10.3138%252Fchr-002-notes.zip&file=10.3138%252Fchr-01-02-03.pdf

(1813) 53 Geo. III, C. 3 (U.C.). UC.1813.ch_.3_0.pdf